Diferencia entre revisiones de «Función compuesta»

Sin resumen de edición |

Al usar un método de anclas se pierde la información de que faltaban tres referencias |

||

| Línea 112: | Línea 112: | ||

* (''f'' ∘ ''f'' ∘ ''f'' ∘ ''f'')(x) = ''f''(''f''(''f''(''f''(''x'')))) = ''f'' <sup>4</sup>(''x'') |

* (''f'' ∘ ''f'' ∘ ''f'' ∘ ''f'')(x) = ''f''(''f''(''f''(''f''(''x'')))) = ''f'' <sup>4</sup>(''x'') |

||

Más generalmente, para cualquier [[número natural]] {{math|''n'' ≥ 2}}, la {{mvar|n}}ésima ''' [[Potencia de un conjunto| potenciación]] funcional''' puede definirse inductivamente por {{math|1=''f'' <sup>''n''</sup> = ''f'' ∘ ''f'' <sup>''n''-1</sup> = ''f''  <sup>''n''-1</sup> ∘ ''f''}}, una notación introducida por [[Hans Heinrich Bürmann]]{{cn|fecha=Agosto 2020|razón=El hecho es indiscutible, pero para completar la historia, encontremos el trabajo original de Bürmann sobre esto y añadámoslo aquí como cita. Debe datarse significativamente antes de 1813 (según Herschel en 1820 y Cajori en 1929.)}} |

Más generalmente, para cualquier [[número natural]] {{math|''n'' ≥ 2}}, la {{mvar|n}}ésima ''' [[Potencia de un conjunto| potenciación]] funcional''' puede definirse inductivamente por {{math|1=''f'' <sup>''n''</sup> = ''f'' ∘ ''f'' <sup>''n''-1</sup> = ''f''  <sup>''n''-1</sup> ∘ ''f''}}, una notación introducida por [[Hans Heinrich Bürmann]]{{cn|fecha=Agosto 2020|razón=El hecho es indiscutible, pero para completar la historia, encontremos el trabajo original de Bürmann sobre esto y añadámoslo aquí como cita. Debe datarse significativamente antes de 1813 (según Herschel en 1820 y Cajori en 1929.)}}{{refn|name="Herschel_1820"|{{cite book |author-first=John Frederick William |author-last=Herschel |author-link=John Frederick William Herschel |title=A Collection of Examples of the Applications of the Calculus of Finite Differences |chapter=Part III. Section I. Examples of the Direct Method of Differences |location=Cambridge, UK |publisher=Printed by J. Smith, sold by J. Deighton & sons |date=1820 |pages=1–13 [5–6] |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PWcSAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA5 |access-date=2020-08-04|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200804031020/https://books.google.de/books?hl=de&id=PWcSAAAAIAAJ&jtp=5 |archive-date=2020-08-04}} [https://archive.org/details/acollectionexam00lacrgoog] (NB. Inhere, Herschel refers to his {{Harvsp|Herschel|1813|texto=1813 work}} and mentions [[Hans Heinrich Bürmann]]'s older work.)}}{{refn|name="Cajori_1929"|{{cite book |author-first=Florian |author-last=Cajori |author-link=Florian Cajori |title=A History of Mathematical Notations |chapter=§472. The power of a logarithm / §473. Iterated logarithms / §533. John Herschel's notation for inverse functions / §535. Persistence of rival notations for inverse functions / §537. Powers of trigonometric functions |volume=2 |publisher=[[Open court publishing company]] |location=Chicago, USA |date=1952 |edition=3rd corrected printing of 1929 issue, 2nd (1st Edition: March 1929)|pages=108, 176–179, 336, 346 |isbn=978-1-60206-714-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bT5suOONXlgC |access-date=2016-01-18 |quote=[…] §473. ''Iterated logarithms'' […] We note here the symbolism used by [[Alfred Pringsheim|Pringsheim]] and [[Jules Molk|Molk]] in their joint ''Encyclopédie'' article: "<sup>2</sup>log<sub>''b''</sub> ''a'' = log<sub>''b''</sub> (log<sub>''b''</sub> ''a''), …, <sup>''k''+1</sup>log<sub>''b''</sub> ''a'' = log<sub>''b''</sub> (<sup>''k''</sup>log<sub>''b''</sub> ''a'')."{{Harvnp|Pringsheim|Molk|1907}} […] §533. ''[[John Frederick William Herschel|John Herschel]]'s notation for inverse functions,'' sin<sup>−1</sup> ''x'', tan<sup>−1</sup> ''x'', etc., was published by him in the ''[[Philosophical Transactions of London]]'', for the year 1813. He says ({{Harvsp|Herschel|1813|texto=p. 10}}): "This notation cos.<sup>−1</sup> ''e'' must not be understood to signify 1/cos. ''e'', but what is usually written thus, arc (cos.=''e'')." He admits that some authors use cos.<sup>''m''</sup> ''A'' for (cos. ''A'')<sup>''m''</sup>, but he justifies his own notation by pointing out that since ''d''<sup>2</sup> ''x'', Δ<sup>3</sup> ''x'', Σ<sup>2</sup> ''x'' mean ''dd'' ''x'', ΔΔΔ ''x'', ΣΣ ''x'', we ought to write sin.<sup>2</sup> ''x'' for sin. sin. ''x'', log.<sup>3</sup> ''x'' for log. log. log. ''x''. Just as we write ''d''<sup>−''n''</sup> V=∫<sup>''n''</sup> V, we may write similarly sin.<sup>−1</sup> ''x''=arc (sin.=''x''), log.<sup>−1</sup> ''x''.=c<sup>''x''</sup>. Some years later Herschel explained that in 1813 he used ''f''<sup>''n''</sup>(''x''), ''f''<sup>−''n''</sup>(''x''), sin.<sup>−1</sup> ''x'', etc., "as he then supposed for the first time. The work of a German Analyst, [[Hans Heinrich Bürmann|Burmann]], has, however, within these few months come to his knowledge, in which the same is explained at a considerably earlier date. He[Burmann], however, does not seem to have noticed the convenience of applying this idea to the inverse functions tan<sup>−1</sup>, etc., nor does he appear at all aware of the inverse calculus of functions to which it gives rise." Herschel adds, "The symmetry of this notation and above all the new and most extensive views it opens of the nature of analytical operations seem to authorize its universal adoption."<ref name="Herschel_1820"/> […] §535. ''Persistence of rival notations for inverse function.''— […] The use of Herschel's notation underwent a slight change in [[Benjamin Peirce]]'s books, to remove the chief objection to them; Peirce wrote: "cos<sup>[−1]</sup> ''x''," "log<sup>[−1]</sup> ''x''."{{Harvnp|Peirce|1852}} […] §537. ''Powers of trigonometric functions.''—Three principal notations have been used to denote, say, the square of sin ''x'', namely, (sin ''x'')<sup>2</sup>, sin ''x''<sup>2</sup>, sin<sup>2</sup> ''x''. The prevailing notation at present is sin<sup>2</sup> ''x'', though the first is least likely to be misinterpreted. In the case of sin<sup>2</sup> ''x'' two interpretations suggest themselves; first, sin ''x'' · sin ''x''; second,{{Harvnp|Peano|1903}} sin (sin ''x''). As functions of the last type do not ordinarily present themselves, the danger of misinterpretation is very much less than in case of log<sup>2</sup> ''x'', where log ''x'' · log ''x'' and log (log ''x'') are of frequent occurrence in analysis. […] The notation sin<sup>''n''</sup> ''x'' for (sin ''x'')<sup>''n''</sup> has been widely used and is now the prevailing one. […]}} (xviii+367+1 pages including 1 addenda page) (NB. ISBN and link for reprint of 2nd edition by Cosimo, Inc., New York, USA, 2013.)}} y [[John Frederick William Herschel]]<!-- en 1813 -->. <ref name="Herschel_1813"/><ref name="Herschel_1820"/><ref name="Peano_1903">{{cite book |author-first=Giuseppe |author-last=Peano |author-link=Giuseppe Peano |title=Formulaire mathématique |language=fr |volume=IV |date=1903 |page=229}}</ref><ref name="Cajori_1929"/> La composición repetida de una función de este tipo consigo misma se denomina '''[[función iterada]]'''. |

||

* Por convención, {{math|''f'' <sup>0</sup>}} se define como el mapa identidad en el dominio de {{math|''f'' }}, {{math|id<sub>''X''</sub>}}. |

* Por convención, {{math|''f'' <sup>0</sup>}} se define como el mapa identidad en el dominio de {{math|''f'' }}, {{math|id<sub>''X''</sub>}}. |

||

* Si incluso {{math|1=''Y'' = ''X''}} y {{math|''f'': ''X'' → ''X''}} admite una [[función inversa]] {{math|''f'' <sup>-1</sup>}}, las potencias funcionales negativas {{math|''f'' <sup>-''n''</sup>}} se definen para {{math|''n'' > 0}} como la [[Opuesto| opuesta]] potencia de la función inversa: {{math|1=''f'' <sup>-''n''</sup> = (''f'' <sup>-1</sup>)<sup>''n''</sup>}}.<ref name="Herschel_1813">{{cite journal |author-first=John Frederick William |author-last=Herschel |author-link=John Frederick William Herschel |title=On a Remarkable Application of Cotes's Theorem |journal=[[Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London]] |publisher=[[Royal Society of London]], printed by W. Bulmer and Co., Cleveland-Row, St. James's, sold by G. and W. Nicol, Pall-Mall |location=London |volume=103 |number=Part 1 |date=1813 |orig-year= |jstor=107384 |pages=8–26 [10]|doi= |s2cid=118124706 |doi-access= }}</ref><ref name="Herschel_1820"/><ref name="Cajori_1929"/> |

* Si incluso {{math|1=''Y'' = ''X''}} y {{math|''f'': ''X'' → ''X''}} admite una [[función inversa]] {{math|''f'' <sup>-1</sup>}}, las potencias funcionales negativas {{math|''f'' <sup>-''n''</sup>}} se definen para {{math|''n'' > 0}} como la [[Opuesto| opuesta]] potencia de la función inversa: {{math|1=''f'' <sup>-''n''</sup> = (''f'' <sup>-1</sup>)<sup>''n''</sup>}}.<ref name="Herschel_1813">{{cite journal |author-first=John Frederick William |author-last=Herschel |author-link=John Frederick William Herschel |title=On a Remarkable Application of Cotes's Theorem |journal=[[Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London]] |publisher=[[Royal Society of London]], printed by W. Bulmer and Co., Cleveland-Row, St. James's, sold by G. and W. Nicol, Pall-Mall |location=London |volume=103 |number=Part 1 |date=1813 |orig-year= |jstor=107384 |pages=8–26 [10]|doi= |s2cid=118124706 |doi-access= }}</ref><ref name="Herschel_1820"/><ref name="Cajori_1929"/> |

||

| Línea 153: | Línea 153: | ||

==Referencias== |

==Referencias== |

||

{{Listaref|2}} |

{{Listaref|2}} |

||

== Bibliografía == |

|||

* {{cite book |author-first=Giuseppe |author-last=Peano |author-link=Giuseppe Peano |title=Formulaire mathématique |language=fr |volume=IV |date=1903 |page=229}} |

|||

* {{cite book |author-first=Benjamin |author-last=Peirce |author-link=Benjamin Peirce |title=Curves, Functions and Forces |volume=I |edition=new |location=Boston, USA |date=1852 |page=203}} |

|||

* {{cite book |author-first1=Alfred |author-last1=Pringsheim |author-link1=Alfred Pringsheim |author-first2=Jules |author-last2=Molk |author-link2=Jules Molk |title=Encyclopédie des sciences mathématiques pures et appliquées |language=fr |id=Part I |volume=I |date=1907 |page=195}} |

|||

== Enlaces externos == |

== Enlaces externos == |

||

Revisión del 21:28 24 abr 2023

En álgebra abstracta, una función compuesta es una función formada por la composición o aplicación sucesiva de otras dos funciones. Para ello, se aplica sobre el argumento la función más próxima al mismo, y al resultado del cálculo anterior se le aplica finalmente la función restante.

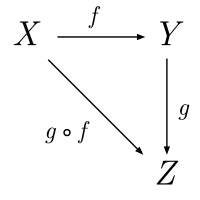

Usando la notación matemática, la función compuesta g ∘ f: X → Z expresa que (g ∘ f)(x) = g[f(x)] para todo x perteneciente a X. Se lee "f compuesta con g", "f en g", "f entonces g", "g de f" o "g círculo f". F°G= F[g(x)] significa que x pertenece al dominio de g y que g(x) pertenece al de F.

La composición de funciones es un caso especial de la composición de relaciones, a veces también denotada por . Como resultado, todas las propiedades de la composición de relaciones son ciertas para la composición de funciones, como la propiedad de asociabilidad.[1]

La composición de funciones es diferente de la multiplicación de funciones (si es que se define), y tiene algunas propiedades bastante diferentes; en particular, la composición de funciones no es comutativa.[2]

Definición

De manera formal, dadas dos funciones:

y

donde la imagen de f está contenida en el dominio de g, se define la función composición de f con g (nótese que las funciones se nombran en el orden de aplicación a la variable, no en el orden sucesivo de representación):

A todos los elementos de X se le asocia una elemento de Z según: .

También se puede representar de manera gráfica usando la categoría de conjuntos, mediante un diagrama conmutativo:

Propiedades

- La composición de funciones es asociativa, es decir:

La composición de funciones es siempre asociativa-una propiedad heredada de la composición de relaciones.[1] Es decir, si f, g, y h son componibles, entonces f ∘ (g ∘ h) = (f ∘ g) ∘ h. [3] Dado que los paréntesis no cambian el resultado, generalmente se omiten.

- La composición de funciones en general no es conmutativa, es decir:

- Por ejemplo, dadas las funciones numéricas f(x)=x+1 y g(x)=x², entonces f(g(x))=x²+1, en tanto que g(f(x))=(x+1)².

- El elemento neutro y también asociado a la composición de funciones es la función identidad.

- Con las tres propiedades anteriores: asociativa, no conmutativa y elemento neutro, las funciones reales de variable real constituyen un monoide para la operación interna de composición de funciones.

- Además, la inversa de la composición de dos funciones es:

En un sentido estricto, la composición g ∘ f sólo tiene sentido si el codominio de f es igual al dominio de g; en un sentido más amplio, basta con que el primero sea un subconjunto impropio del segundo.[nb 1] Además, a menudo es conveniente restringir tácitamente el dominio de f, de modo que f produzca sólo valores en el dominio de g. Por ejemplo, la composición g ∘ f} de las funciones f : R → (-∞,+9] definidas por f(x) = 9 - x2} y g : [0,+∞)] → R definidas por pueden definirse en el intervalo [-3,+3].

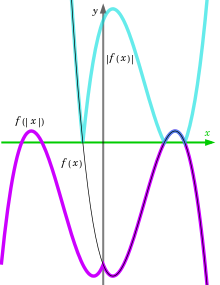

Se dice que las funciones g y f son conmutativas entre sí si g ∘ f = f ∘ g. La conmutatividad es una propiedad especial, alcanzada sólo por funciones particulares, y a menudo en circunstancias especiales. Por ejemplo, x + 3 = |x| + 3 sólo cuando x ≥ 0. La imagen muestra otro ejemplo.

La composición de funciones uno a uno (inyectivas) es siempre uno a uno. Del mismo modo, la composición de onto (sobreyectiva) funciones es siempre onto. De ello se deduce que la composición de dos biyecciones es también una biyección. La función inversa de una composición (se supone invertible) tiene la propiedad de que (f ∘ g)-1 = g-1∘ f-1.[4]

Las Derivadass de composiciones que involucran funciones diferenciables pueden hallarse usando la regla de la cadena. Las derivadas superiores de tales funciones vienen dadas por fórmula de Faà di Bruno.[3]

Monoides de composición

Supongamos que tenemos dos (o más) funciones f: X → X, g: X → X que tienen el mismo dominio y codominio; a menudo se llaman transformaciones'. Entonces se pueden formar cadenas de transformaciones compuestas entre sí, como f ∘ f ∘ g ∘ f. Tales cadenas tienen la estructura algebraica de un monoide, llamado un monoide de transformación o (mucho más raramente) un monoide de composición. En general, los monoides de transformación pueden tener una estructura notablemente complicada. Un ejemplo notable es la curva de De Rham. El conjunto de todas las funciones f: X → X} se llama el semigrupo de transformación completa[5] o semigrupo simétrico[6] en X. (En realidad se pueden definir dos semigrupos dependiendo de cómo se defina la operación de semigrupo como composición izquierda o derecha de funciones.[7]).

Si las transformaciones son biyectivas (y por tanto invertibles), entonces el conjunto de todas las combinaciones posibles de estas funciones forma un grupo de transformaciones; y se dice que el grupo es generado por estas funciones. Un resultado fundamental en la teoría de grupos, el teorema de Cayley, esencialmente dice que cualquier grupo es de hecho sólo un subgrupo de un grupo de permutación (hasta isomorfismo).[8]

El conjunto de todas las funciones biyectivas f: X → X} (llamadas permutaciones) forma un grupo con respecto a la composición de funciones. Este es el grupo simétrico, también llamado a veces grupo de composición.

En el semigrupo simétrico (de todas las transformaciones) también se encuentra una noción más débil y no única de inversa (llamada pseudoinversa) porque el semigrupo simétrico es un semigrupo regular.[9]

Ejemplos

- Composición de funciones sobre un conjunto finito: Si f = {(1, 1), (2, 3), (3, 1), (4, 2)}, y g = {(1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 1), (4, 2)}, entonces g ∘ f = {(1, 2), (2, 1), (3, 2), (4, 3)}, como se muestra en la figura.

- Composición de funciones sobre un conjunto infinito: Si f: R → R (donde R es el conjunto de todos los números reales) viene dada por f(x) = 2x + 4 y g: R → R viene dada por g(x) = x3, entonces:

(f ∘ g)(x) = f(g(x)) = f(x3) = 2x3 + 4, y

(g ∘ f)(x) = g(f(x)) = g(2x' + 4) = (2x + 4)3

- Si la altitud de un avión en el momento t es a(t), y la presión atmosférica a la altitud x es p(x), entonces (p ∘ a)(t) es la presión alrededor del avión en el tiempo t.

Sean las funciones:

La función compuesta por ende x de g y de f que expresamos:

La interpretación de (f ∘ g) aplicada a la variable x significa que primero tenemos que aplicar g a x, con lo que obtendríamos un valor de paso

y después aplicamos f a z para obtener

Potencias funcionales

Si Y ⊆ X, entonces f: X→Y puede componerse consigo mismo; esto se denota a veces como f 2. Es decir:

- (f ∘ f)(x) = f(f(x)) = f 2(x)

- (f ∘ f ∘ f)(x) = f(f(f(x))) = f 3(x)

- (f ∘ f ∘ f ∘ f)(x) = f(f(f(f(x)))) = f 4(x)

Más generalmente, para cualquier número natural n ≥ 2, la nésima potenciación funcional puede definirse inductivamente por f n = f ∘ f n-1 = f n-1 ∘ f, una notación introducida por Hans Heinrich Bürmann[cita requerida][10][14] y John Frederick William Herschel. [15][10][16][14] La composición repetida de una función de este tipo consigo misma se denomina función iterada.

- Por convención, f 0 se define como el mapa identidad en el dominio de f , idX.

- Si incluso Y = X y f: X → X admite una función inversa f -1, las potencias funcionales negativas f -n se definen para n > 0 como la opuesta potencia de la función inversa: f -n = (f -1)n.[15][10][14]

Función bien definida

La función compuesta está bien definida porque cumple con las dos condiciones de existencia y unicidad, propias de toda función:

- Condición de existencia: dado x, conocemos (x, f(x)), puesto que conocemos la función f, y dado cualquier elemento y de B conocemos también (y, g(y)), puesto que conocemos la función g. Por tanto, (x, g( f(x)) ) está definido para todo x, y así (g ∘ f) cumple la condición de existencia.

- Condición de unicidad: como f y g son funciones bien definidas, para cada x el valor de f(x) es único, y para cada f(x) también lo es el de g(f(x)).

Funciones de varias variables

Es posible la composición parcial de funciones de variables múltiples. La función resultante cuando algún argumento xi de la función f es reemplazado por la función g es denominada una composición de f y g en algunos contextos de ingeniería computacional, y se expresa como f |xi = g

Cuando g es una constante simple b, la composición se degenera en una evaluación (parcial), cuyo resultado también es denominado restricción o co-factor.[17]

En general, la composición de funciones de múltiples variables puede comprender varias otras funciones como argumentos, como es el caso en la definición de función primitiva recursiva. Dado f, y una función de n-iables, y las funciones de n m variables g1, ..., gn, la composición de f con g1, ..., gn, es la función de m variables

A veces ello es denominado la compuesta generalizada o superposición de f con g1, ..., gn.[18] La composición parcial en un solo argumento mencionada previamente puede ser representada a partir de este esquema más general asignando todas las funciones argumentos excepto una para ser funciones proyectivas convenientemente elegidas. En este caso g1, ..., gn puede ser aimilado a una función evaluada vector/tupla en este esquema generalizado, en cuyo caso esto es precisamente la definición estándar de composición de función.[19]

Un conjunto de operaciones finitas en alguna base X es denominada un clon si contiene todas las proyecciones y es cerrado para una composición generalizada. Es de notar que un clon generalmente contiene operaciones de varias aridades.[18] La noción de conmutación también encuentra una interesante generalización en el caso multivariante; se dice que una función f de aridad n conmuta con una función g de aridad m si f es un homomorfismo que preserva g, y viceversa, es decir:[18]

Una operación unaria siempre conmuta consigo misma, pero no es necesariamente el caso de una operación binaria (o de aridad superior). Una operación binaria (o de aridad superior) que conmuta consigo misma se llama medial o entrópica.[18]

Monoides de composición

Supongamos que tenemos dos (o más) funciones f: X → X, g: X → X que tienen el mismo dominio y codominio; a menudo se llaman transformaciones'. Entonces se pueden formar cadenas de transformaciones compuestas entre sí, como f ∘ f ∘ g ∘ f. Tales cadenas tienen la estructura algebraica de un monoide, llamado un monoide de transformación o (mucho más raramente) un monoide de composición. En general, los monoides de transformación pueden tener una estructura notablemente complicada. Un ejemplo notable es la curva de De Rham. El conjunto de todas las funciones f: X → X} se llama el semigrupo de transformación completa[5] o semigrupo simétrico[6] en X. (En realidad se pueden definir dos semigrupos dependiendo de cómo se defina la operación de semigrupo como composición izquierda o derecha de funciones.[7]

Potencias funcionales

Si Y ⊆ X, entonces f: X→Y puede componerse consigo misma; esto se denota a veces como f 2. Es decir:

- (f ∘ f)(x) = f(f(x)) = f 2(x)

- f ∘ f ∘ f)(x) = f(f(f(x))) = f 3(x)

- (f ∘ f ∘ f ∘ f)(x) = f(f(f(f(x)))) = f 4(x)

Notas

- ↑ Se utiliza el sentido estricto, p. ej., en la teoría de categorías, donde una relación de subconjunto se modela explícitamente mediante una inyección canónica.

Referencias

- ↑ a b Velleman, Daniel J. (2006). How to Prove It: A Structured Approach. Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-139-45097-3.

- ↑ «3.4: Composición de funciones». Mathematics LibreTexts (en inglés). 16 de enero de 2020. Consultado el 28 de agosto de 2020.

- ↑ a b Weisstein, Eric W. «Composition». mathworld.wolfram.com. Consultado el 28 de agosto de 2020.

- ↑ Rodgers, Nancy (2000). Learning to Reason: An Introduction to Logic, Sets, and Relations. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 359-362. ISBN 978-0-471-37122-9.

- ↑ a b Hollings, Christopher (2014). Mathematics across the Iron Curtain: A History of the Algebraic Theory of Semigroups. American Mathematical Society. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-4704-1493-1.

- ↑ a b Grillet, Pierre A. (1995). Semigroups: An Introduction to the Structure Theory. CRC Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8247-9662-4.

- ↑ a b Dömösi, Pál; Nehaniv, Chrystopher L. (2005). Algebraic Theory of Automata Networks: An introduction. SIAM. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-89871-569-9.

- ↑ Carter, Nathan (9 de abril de 2009). Visual Group Theory. MAA. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-88385-757-1.

- ↑ Ganyushkin, Olexandr; Mazorchuk, Volodymyr (2008). Classical Finite Transformation Semigroups: An Introduction. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84800-281-4.

- ↑ a b c d Herschel, John Frederick William (1820). «Part III. Section I. Examples of the Direct Method of Differences». A Collection of Examples of the Applications of the Calculus of Finite Differences. Cambridge, UK: Printed by J. Smith, sold by J. Deighton & sons. pp. 1–13 [5–6]. Archivado desde el original el 4 de agosto de 2020. Consultado el 4 de agosto de 2020. [1] (NB. Inhere, Herschel refers to his 1813 work and mentions Hans Heinrich Bürmann's older work.)

- ↑ Pringsheim y Molk, 1907.

- ↑ Peirce, 1852.

- ↑ Peano, 1903.

- ↑ a b c Cajori, Florian (1952). «§472. The power of a logarithm / §473. Iterated logarithms / §533. John Herschel's notation for inverse functions / §535. Persistence of rival notations for inverse functions / §537. Powers of trigonometric functions». A History of Mathematical Notations 2 (3rd corrected printing of 1929 issue, 2nd (1st Edition: March 1929) edición). Chicago, USA: Open court publishing company. pp. 108, 176-179, 336, 346. ISBN 978-1-60206-714-1. Consultado el 18 de enero de 2016. «[…] §473. Iterated logarithms […] We note here the symbolism used by Pringsheim and Molk in their joint Encyclopédie article: "2logb a = logb (logb a), …, k+1logb a = logb (klogb a)."[11] […] §533. John Herschel's notation for inverse functions, sin−1 x, tan−1 x, etc., was published by him in the Philosophical Transactions of London, for the year 1813. He says (p. 10): "This notation cos.−1 e must not be understood to signify 1/cos. e, but what is usually written thus, arc (cos.=e)." He admits that some authors use cos.m A for (cos. A)m, but he justifies his own notation by pointing out that since d2 x, Δ3 x, Σ2 x mean dd x, ΔΔΔ x, ΣΣ x, we ought to write sin.2 x for sin. sin. x, log.3 x for log. log. log. x. Just as we write d−n V=∫n V, we may write similarly sin.−1 x=arc (sin.=x), log.−1 x.=cx. Some years later Herschel explained that in 1813 he used fn(x), f−n(x), sin.−1 x, etc., "as he then supposed for the first time. The work of a German Analyst, Burmann, has, however, within these few months come to his knowledge, in which the same is explained at a considerably earlier date. He[Burmann], however, does not seem to have noticed the convenience of applying this idea to the inverse functions tan−1, etc., nor does he appear at all aware of the inverse calculus of functions to which it gives rise." Herschel adds, "The symmetry of this notation and above all the new and most extensive views it opens of the nature of analytical operations seem to authorize its universal adoption."[10] […] §535. Persistence of rival notations for inverse function.— […] The use of Herschel's notation underwent a slight change in Benjamin Peirce's books, to remove the chief objection to them; Peirce wrote: "cos[−1] x," "log[−1] x."[12] […] §537. Powers of trigonometric functions.—Three principal notations have been used to denote, say, the square of sin x, namely, (sin x)2, sin x2, sin2 x. The prevailing notation at present is sin2 x, though the first is least likely to be misinterpreted. In the case of sin2 x two interpretations suggest themselves; first, sin x · sin x; second,[13] sin (sin x). As functions of the last type do not ordinarily present themselves, the danger of misinterpretation is very much less than in case of log2 x, where log x · log x and log (log x) are of frequent occurrence in analysis. […] The notation sinn x for (sin x)n has been widely used and is now the prevailing one. […]». (xviii+367+1 pages including 1 addenda page) (NB. ISBN and link for reprint of 2nd edition by Cosimo, Inc., New York, USA, 2013.)

- ↑ a b Herschel, John Frederick William (1813). «On a Remarkable Application of Cotes's Theorem». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (London: Royal Society of London, printed by W. Bulmer and Co., Cleveland-Row, St. James's, sold by G. and W. Nicol, Pall-Mall) 103 (Part 1): 8–26 [10]. JSTOR 107384. S2CID 118124706.

- ↑ Peano, Giuseppe (1903). Formulaire mathématique (en francés) IV. p. 229.

- ↑ Bryant, R. E. (August 1986). «Logic Minimization Algorithms for VLSI Synthesis». IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-35 (8): 677-691. S2CID 10385726. doi:10.1109/tc.1986.1676819.

- ↑ a b c d Bergman, Clifford (2011). Universal Algebra: Fundamentals and Selected Topics. CRC Press. pp. 79–80, 90–91. ISBN 978-1-4398-5129-6.

- ↑ Tourlakis, George (2012). Theory of Computation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-118-31533-0.

Bibliografía

- Peano, Giuseppe (1903). Formulaire mathématique (en francés) IV. p. 229.

- Peirce, Benjamin (1852). Curves, Functions and Forces I (new edición). Boston, USA. p. 203.

- Pringsheim, Alfred; Molk, Jules (1907). Encyclopédie des sciences mathématiques pures et appliquées (en francés) I. p. 195. Part I.

Enlaces externos

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Composition». En Weisstein, Eric W, ed. MathWorld (en inglés). Wolfram Research.

- "Composition of Functions" by Bruce Atwood, the Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.