Usuario:Ivan de la Mora/Mysteries of Isis

Los misterios de Isis son unos ritos de iniciación religiosa que se hacían en culto a la diosa Isis en el mundo Greco-Romano. Están basados en otros ritos misteriosos, particularmente en los misterios Eleusinos, en honor a la diosa Griega Demeter y se originaron alrededor del siglo III a.C. y el siglo II d.C. A pesar de sus origenes helenicos, los misterios se remontan a la antigua religión egipcia, en donde se adoraba a Isis. Al seguir estos mitos, los iniciados demostraban su devoción a Isis, aunque no necesariamente dedicaban los ritos solo a esta diosa. Los ritos eran vistos como un simbolo de muerte y resurrección, lo que en esa epoca se creia que garantizaba, con la ayuda de la diosa, el paso del alma del iniciado a la segunda vida.

Muchos textos del Imperio Romano hacen referencia a estos mitos, pero la única fuente que los describe es la novela Metamorfosis, escrita en el siglo II por Apuleius. En esta, el iniciado pasa por un elaborado proceso de purificación antes de poder descender a la parte mas profunda del templo de Isis, en donde lleva a cabo una intensa experiencia religiosa en la que ve a los dioses directamente.

Algunos aspectos de los misterios de Isis y otros cultos, particularmente su conexión con la vida mas allá de la muerte, tienen semejanzas con el Cristianismo. La cuestión de si los misterios influenciaron los ritos cristianos es controversial y las pruebas no son claras; algunos eruditos contemporáneos atribuyen algunas de estas similitudes con la cultura compartida de la que ambos ritos vienen, mas que de una influencia directa. En contraste, Apuleius tiene influencia hoy en día. Mediante esta descripción, los misterios de Isis han influenciado muchas obras de ficción actuales y fraternidades de organizaciones actuales, así como extendiendo de manera errónea, la creencia de que los egipcios antiguos tenían un misterioso sistema de mitos de iniciación.

Orígenes[editar]

Los misterios Greco-Romanos eran, en palabras del clasicista Walter Burkert, "rituales de iniciacion voluntarios, personales y secretos con la intención de formar un cambio en el caracter de un individuo por medio de una experiencia sagrada".[2] Estos ritos en especial estaban dedicados a un grupo de deidades especificas y eran usados como un amplio grupo de intensas experiencias, como cuando se interrumpe la tranquilidad y obscuridad de la noche con luz cegadora, musica y sonido, cosa que inducía un estado de desorientación y una fuerte experiencia religiosa. Algunos de estos rituales involucraban simbolismo críptico. Los iniciados no se suponía que discutieran lo que experimentaban en los ritos, cosa que justifica los secretos y falta de información al respecto en tiempos modernos.[3] Los misterios mas prestigiosos del mundo girego eran los misterios Eleusinos dedicados a la diosa Demeter, que se llevaban a cavo en Eleusis, cerca de Atenas, desde al menos el siglo VI a.C[4]. hasta el final del siglo IV d.C.[5] Estaban centrados en la busqueda de Demeter por su hija Persephone en la mitología griega.[6] Los iniciados de estos ritos pasaban a un pasillo obscuro, llamado Telesterion y eran expuestos a escenas terribles, seguidos por una luz cegadora y gritos del hierofante que llevaba la ceremonia. Con esta luz los iniciados veían objetos que representaban el poder de Demeter con respecto a la fertilidad, así como una gavilla de trigo y tal vez algunas otras imagenes referentes al mito de Perspephone.[6] En los misterios del dios Dionisio, que se llebavan a cabo en muchos lugares del mundo griego, los participantes celebraban en una gran fiesta de noche al aire libre.[7] Estas celebraciones estaban conectadas en cierta manera con el orfismo, un grupo de creencias misticas acerca de la naturaleza después de la muerte.[8]

Isis originalmente era una diosa el una antigua religion egipcia, que no incluía la serie de misterios griegos. Algunos rituales egipcios eran hechos exclusivamente por sacerdotes, fuera del conocimiento publico, pero la gente egipcia nunca era admitida en esas celebraciones.[9] Otros rituales pudieron hacer sido retomados de la mitología griega, como ceremonias en honor a Osiris, el dios de la vida después de la muerte y esposo de Isis, que se llevaban a cabo en Abydos.[10] Los griegos interpretaban estos mitos basados en rituales como misterios. El historiador Heredotus, fue el primero en escribir al respecto en el siglo V a.C. El hace referencia a los mitos del asesinato de Osiris como misterios, relacionándolos con los misterios de Dionisio, mismos con los que el estaba muy familiarizado.[11] Escribió acerca de que la adoración a Dionisio fue influenciada con los mitos de Osiris en Egipto.[12] Muchos escritores egipcios posteriores a Herodotus veían Egipto y a sus sacerdotes como la fuente de toda la sabiduría mística.[13] Estos aseguraban que muchos de los elementos filosóficos griegos tenían origen en la cultura egipcia, [14] incluidos los misterios de los cultos.[9] Burkert y el egiptologo Francesco Tiradritti decian que existe algo de verdad en estas teorias, ya que los cultos de misterios griegos mas antiguos de los que se tiene registro se remontan a los siglos VI y VII a.C, epoca en la que Grecia estaba estableciendo considerablemente mayor con la cultura egipcia. Las imagenes y representaciones de la vida después de la muerte encontradas en los misterios de cultos pueden haber sido influenciadas por las creencias egipcias de este tema en particular.[12][15]

Isis era una de las deidades no griegas cuyo culto se volvió parte de la religion Griega y romana durante el periodo helénico (323 a 30 a.C.), cuando la gente griega y su cultura se expandieron a lo largo de Mediterraneo y la mayoría de estos lugares fueron conquistados por la República Romana. Bajo la influencia de las tradiciones greco-romanas, algunos de estos cultos, entre estos el de Isis, desarrollaron sus propios ritos.[16] Los misterios de Isis pudieron emerger desde el siglo III a.C, después de que la dinastia Ptolomeica tomara control sobre Egipto. Los Ptolomies promovieron el culto al dios Serapis, que incorporo algunas caracteristicas de Osiris y de deidades como Dionisio y el dios del inframundo Pluton. El culto a Isis se fusiono con el de Serapis. Ella estaba demasiado interpretada para asemejarse a a las diosas griegas, en especial a Demeter, mientras que retenia muchas de sus caracteristicas egipcias. Los misterios de Isis, modelados en honor a Demeter por los Eleusios, pudieron haber sido desarrollados al mismo tiempo, como parte de una fusión de las religiones griegas y egipcias.[17][Note 1]

Otra posibilidad es que los misterios se desarrollaran después de que el culto de Isis helenizada llegara a Grecia, en el siglo III a.C. Mucha de la evidencia temprana del culto a Isis en Grecia proviene de aretalogías, poemas que alaban a los dioses. Las palabras de las aratelogías de Maroneia y Andros, del primer siglo a.C, están muy relacionadas con los ritos misteriosos. Petra Pakkanen dice que estas aretalogias prueban que los misterios de Isis ya existían para esa época, [19] pero Jan Bremmer argumenta que esto solo conecta a Isis con los misterios Eleusinos, no con ritos distintos por si solos.[20] Existe evidencia fuerte de que los misterios ya existian en el siglo I a.C.[21] Los templos de Isis en Grecia pueden haber desarrollado sus misterios en respuesta a la expansión de las creencias griegas de que estos mitos se habían originado en Egipto. Estos pudieron adapatarse a los ritos Eleusinos, probablemente también de los misterios de Dionisio, para reflejarla mitología egipcia. El producto final hubiera parecido a los griegos como que los mitos egipcios fueron el origen de los misterios giregos.[22][23] Muchas fuentes greco-romanos afirman que Isis misma fue la que enseño estos ritos.[24]

Una vez establecidos estos misterios, no se realizaban en todos los lugares de adoración a Isis. Los unicos lugares conocidos donde se realizaban estos ritos fueron Italia, Grecia y Anatolia, [21] aunque se le adoraba en casi todas las provincias del Imperio Romano.[25] En Egipto existen solo algunos textos e imagenes de la epoca del imperio romano que hacen referencia a los misterios de Isis y no esta claro de que alguna vez se llevaran a cabo ahi.[26]

La descripción de los mitos por Apuleius[editar]

Contexto y credibilidad[editar]

Several texts from Roman times refer to people who were initiated in the Isis cult.

Algunos textos del tiempo de los romanos hacen referencia a gente que fue iniciada en el culto.[21] A pesar de esto, la unica descripción directa de los misterios de Isis viene de Metamorfosis, también conocida como "El asno de oro", una novela cómica de la segunda parte del siglo II a.C, escrita por Apuleius.[27]

El protagonista de la novela es Lucius, un hombre que ha sido transformado magimanete en un asno. En el libro 11 y ultimo de la novela, Lucius, despues de quedarse dormido en la playa de Cenchreae en Grecia, se despierta para ver la luna llena. El reza a la luna, usando los nombres de algunos de los nombres conocidos de las diosas de la luna del mundo greco-romano, pidiendo que se le devuelva su forma humana. Isis aparece en una visión a Lucius y declara que ella es la mejor diosa de todas. Ella le dice que en un festival en su honor, el Navigum Isidis, que se llevara a cabo cerca de donde están, en la ceremonia se llevan unas flores especiales que lo devolveran a su forma humana si las come. Después de que Lucius vuelve a su forma humana, un sacerdote declara en el festival que el ha sido salvado por la caridad de la diosa y que no sera libre hasta pagar con gratitud la deuda contraida por sus aventuras pasadas. Lucius se una el templo local que adora a Isis, se vuelve un seguidor y eventualmente es inciado en los ritos.[28]

Lucius's apparently solemn devotion to the Isis cult in this chapter contrasts strongly with the comic misadventures that make up the rest of the novel. Scholars debate whether the account is intended to seriously represent Lucius's devotion to the goddess, or whether it is ironic, perhaps a satire of the Isis cult. Those who believe it is satirical point to the way Lucius is pushed to undergo several initiations, each requiring a fee, despite having little money.[29] Although many of the scholars who have tried to analyze the mysteries based on the book have assumed it is serious, the book may be broadly accurate even if it is satirical.[30] Apuleius's description of the Isis cult and its mysteries generally fits with much of the outside evidence about them.[29][31] S.J. Harrison says it shows "detailed knowledge of Egyptian cult, whether or not Apuleius himself was in fact an initiate of Isiac religion."[32] In another of his works, the Apologia, Apuleius claims to have undergone several initiations, though he does not mention the mysteries of Isis specifically.[33] In writing Metamorphoses, he may have drawn on personal experience of the Isiac initiation[34] or of other initiations that he underwent.[33] Even so, the detailed description given in Metamorphoses may be idealized rather than strictly accurate, and the Isis cults may have included many varieties of mystery rite. The novel actually mentions three distinct initiation rites in two cities, although only the first is described in any detail.[35]

Rites[editar]

According to Metamorphoses, the initiation "was performed in the manner of voluntary death and salvation obtained by favor."[36] Only Isis herself could determine who should be initiated and when; thus, Lucius only begins preparing for the mysteries after Isis appears to him in a dream.[37] The implication that Isis was thought to command her followers directly is supported by the Greek writer Pausanias, writing in the same era as Apuleius, who said no one was allowed to participate in Isis' festivals in her shrine at Tithorea without her inviting them in a dream,[38] and by inscriptions in which priests of Isis write that she called them to become her servants.[39] In Apuleius's description, the goddess also determines how much the initiate must pay to the temple in order to undergo the rites.[37]

The priests in Lucius's initiation read the procedure for the rite from a ritual book kept in the temple that is covered in "undecipherable letters", some of which are "forms of all kinds of animals" while others are ornate and abstract.[37] The use of a book for ritual purposes was much more common in Egyptian religion than in Greek or Roman tradition, and the characters in them are often thought to be hieroglyphs or hieratic, which in the eyes of Greek and Roman worshippers would emphasize the Egyptian background of the rite and add to its solemnity.[40] However, David Frankfurter suggests that they are akin to the deliberately unintelligible magical symbols that were commonly used in Greco-Roman magic.[41]

Before the initiation proper, Lucius must undergo a series of ritual purifications. The priest bathes him, asks the gods for forgiveness on his behalf, and sprinkles him with water.[42] This confession of and repentance for past sins fits with an emphasis on chastity and other forms of self-denial found in many other sources about the Isis cult.[43] Lucius next has to wait ten days, while abstaining from meat and wine, before the initiation begins.[42] Purifying baths were common in many rituals across the Greco-Roman world. The plea for forgiveness, however, may derive from the oaths that Egyptian priests were required to take, in which they declared themselves to be free of wrongdoing.[44] The sprinkling with water and the refraining from certain foods probably come from the purification rituals that those priests had to undergo before entering a temple.[45] On the evening of the final day, Lucius receives a variety of gifts from fellow devotees of Isis before donning a clean linen robe and entering the deepest part of the temple.[42]

The description of what happens next is deliberately cryptic. Lucius reminds the reader that the uninitiated are not allowed to know the details of the mystery rites, before describing his experience in vague terms.[46]

I came to the boundary of death and, having trodden on the threshold of Proserpina, I travelled through all the elements and returned. In the middle of the night I saw the sun flashing with bright light, I came face to face with the gods below and the gods above and paid reverence to them from close at hand.[47]

In a series of paradoxes, then, Lucius travels to the underworld and to the heavens, sees the sun amid darkness, and approaches the gods.[48] Many people have speculated about how the ritual simulated these impossible experiences. The first sentence indicates that the initiate is supposed to be passing through the Greek underworld, but the surviving remains of Roman temples to Isis have no subterranean passages that might have simulated the underworld. The bright "sun" Lucius mentions may have been a fire in the darkness, similar to the one at the climax of the Eleusinian Mysteries. The gods he saw face to face may have been statues or frescoes of deities.[49] Some scholars believe that the initiation also entailed some kind of reenactment of or reference to the death of Osiris, but if it did, Apuleius's text does not mention it.[50][51]

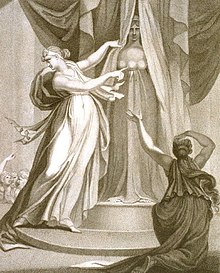

Lucius emerges from this experience in the morning, and the priests dress him in an elaborately embroidered cloak. He then stands on a dais carrying a torch and wearing a crown of palm leaves—"adorned like the sun and set up in the manner of a divine statue", as Apuleius describes it. The priests draw back curtains to reveal Lucius to a crowd of his fellow devotees. During the next three days, Lucius enjoys a series of banquets and sacred meals with his fellow worshippers, completing the initiation process.[52]

After this initiation, Lucius moves to Rome and joins its main temple to the goddess, the Iseum Campense. Urged by more visions sent by the gods, he undergoes two more initiations, incurring more expenses—such as having to buy a replacement for the cloak he left behind at Cenchreae—each time. These initiations are not described in as much detail as the first. The second is dedicated to Osiris and is said to be different from the one dedicated to Isis. Apuleius calls it "the nocturnal ecstasies of the supreme god" but gives no other details. The third initiation may be dedicated to both Isis and Osiris. Before this initiation, Lucius has a vision where Osiris himself speaks to him, suggesting that he is the dominant figure in the rite. At the novel's end Lucius has been admitted to a high position in the cult by Osiris himself, and he is confident that the god will ensure his future success in his work as a lawyer.[53]

Significance[editar]

Religious symbolism and contact with the gods[editar]

Most mystery rites were connected with myths about the deities they focused on—the Osiris myth, in the case of Isis—and they claimed to convey to initiates details about the myths that were not generally known. In addition, various Greco-Roman writers produced theological and philosophical interpretations of the mysteries. Spurred by the fragmentary evidence, modern scholars have often tried to discern what the mysteries may have meant to their initiates.[54] But Hugh Bowden argues that there may have been no single, authoritative interpretation of mystery rites and that "the desire to identify a lost secret—something that, once it is correctly identified, will explain what a mystery cult was all about—is bound to fail."[55] He regards the effort to meet the gods directly, exemplified by the climax of Lucius's initiation in Metamorphoses, as the most important feature of the rites.[56] The notion of meeting the gods face to face contrasted with classical Greek and Roman beliefs,[57] in which seeing the gods, though it might be an awe-inspiring experience, could be dangerous and even deadly.[58] In Greek mythology, for example, the sight of Zeus's true form incinerated the mortal woman Semele. Yet Lucius's meeting with the gods fits with a trend, found in various religious groups in Roman times, toward a closer connection between the worshipper and the gods.[57]

Ancient Egyptian beliefs are one possible source for understanding the symbolism in the mysteries of Isis. J. Gwyn Griffiths, an Egyptologist and classical scholar, extensively studied Book 11 of Metamorphoses and its possible Egyptian background. He pointed out similarities between the first initiation in Metamorphoses and Egyptian afterlife beliefs, saying that the initiate took on the role of Osiris by undergoing symbolic death. In his view, the imagery of the initiation refers to the Egyptian underworld, the Duat.[59] Griffiths argued that the sun in the middle of the night, in Lucius' account of the initiation, might have been influenced by the contrasts of light and dark in other mystery rites, but it derived mainly from the depictions of the underworld in ancient Egyptian funerary texts. According to these texts, the sun god Ra passes through the underworld each night and unites with Osiris to emerge renewed, just as deceased souls do.[60]

The "elements" that Lucius passes through in the first initiation may refer to the classical elements of earth, air, water, and fire that were believed to make up the world,[61] or to regions of the cosmos.[62] In either case, it indicates that Lucius's vision transports him beyond the human world.[61][62] Panayotis Pachis believes the word refers specifically to the planets in Hellenistic astrology.[63] Astrological themes appeared in many other cults in the Roman Empire, including another mystery cult, dedicated to Mithras.[64] In the Isis cult, astrological symbolism may have alluded to the belief that Isis governed the movements of the stars and thus the passage of time and the order of the cosmos, beliefs that Lucius refers to when praying to the goddess.[65]

However, in the course of the book, as Valentino Gasparini puts it, "Osiris explicitly snatches out of Isis's hands the role of Supreme Being" and replaces her as the focus of Lucius's devotion.[66] Osiris' prominence in the Metamorphoses is in keeping with other evidence about the Isis cult in Rome, which suggests that it adopted more themes and imagery from Egyptian funerary religion and the worship of Osiris in the late 1st and early 2nd centuries CE.[67] Gasparini argues that the shift in focus reflects a belief that Osiris was the supreme being and Isis was an intermediary between him and humanity. This interpretation is found in the book On Isis and Osiris by the first-century CE Greek author Plutarch, which analyzes the Osiris myth based on Plutarch's own Middle Platonist philosophy.[66] However, S.J. Harrison suggests that the sudden switch of focus from Isis to Osiris is simply a satire of grandiose claims of religious devotion.[68]

Commitment to the cult[editar]

Because not all local cults of Isis held mystery rites, not all her devotees would have undergone initiation.[69] Nevertheless, both Apuleius's story and Plutarch's On Isis and Osiris suggest that initiation was considered part of the larger process of joining the cult and dedicating oneself to the goddess.[70]

The Isis cult, like most in the Greco-Roman world, was not exclusive; worshippers of Isis could continue to revere other gods as well. Devotees of Isis were among the very few religious groups in the Greco-Roman world to have a distinctive name for themselves, loosely equivalent to "Jew" or "Christian", that might indicate they defined themselves by their exclusive devotion to the goddess. However, the word—Isiacus or "Isiac"—was rarely used.[71] Many priests of Isis officiated in other cults as well. Several people in late Roman times, like Vettius Agorius Praetextatus, joined multiple priesthoods and underwent several initiations dedicated to different gods.[72] Mystery initiations thus did not require devotees to abandon whatever religious identity they originally had, and they would not qualify as religious conversions under a narrow definition of the term. However, some of these initiations did involve smaller changes in religious identity, such as joining a new community of worshippers or strengthening devotees' commitment to a cult they were already part of, that would qualify as conversions in a broader sense.[73] Many ancient sources, both written by Isiacs and by outside observers, suggest that many of Isis's devotees considered her the focus of their lives and that the cult emphasized moral purity, self-denial, and public declarations of devotion to the goddess. Joining Isis's cult was therefore a sharper change in identity than in many other mystery cults. Isiac initiation, by giving the devotee a dramatic, mystical experience of the goddess, added emotional intensity to the process.[74]

It is unclear how initiation may have affected a devotee's rank within the cult.[75] After going through his third initiation, Lucius becomes a pastophoros, a member of a particular class of priests. If the third initiation was a requirement for becoming a pastophoros, it is possible that members moved up in the cult hierarchy by going through the series of initiations.[76] Nevertheless, Apuleius refers to initiates and to priests as if they are separate groups within the cult. Initiation may have been a prerequisite for a devotee to become a priest but not have automatically made him or her into one.[77]

Connection with the afterlife[editar]

Many pieces of evidence suggest that the mysteries of Isis were connected in some way to salvation and the guarantee of an afterlife.[78] The Greek conception of the afterlife included the paradisiacal Elysian Fields, and philosophers developed various ideas about the immortality of the soul, but Greeks and Romans expressed uncertainty about what would happen to them after death. In both Greek and Roman traditional religion, no god was thought to guarantee a pleasant afterlife to his or her worshippers. The gods of some mystery cults may have been exceptions, but evidence about those cults' afterlife beliefs is vague.[79] Apuleius's account, if it is accurate, provides stronger evidence for Isiac afterlife beliefs than is available for the other cults. The book says Isis's power over fate, which her Greek and Roman devotees frequently mentioned, gives her control over life and death.[78] According to the priest who initiates Lucius, devotees of Isis "who had finished their life's span and were already standing on the threshold of light’s end, if only they could safely be trusted with the great unspoken mysteries of the cult, were frequently drawn forth by the goddess' power and in a manner reborn through her providence and set once more on the course of renewed life."[80] In another passage, Isis herself says that when Lucius dies he will be able to see her shining in the darkness of the underworld and worship her there.[81]

Some scholars are skeptical the afterlife was a major focus of the cult.[82] Ramsay MacMullen says that when characters in Metamorphoses call Lucius "reborn", they refers to his new life as a devotee and never call him renatus in aeternam [eternally reborn], which would refer to the afterlife.[83] Mary Beard, John North, and Simon Price say Metamorphoses shows that "the cult of Isis had implications for life and death, but even so more emphasis is placed on extending the span of life than on the after-life—which is pictured in fairly undifferentiated terms."[84]

A funerary inscription from Bithynia, left by a devotee of Isis, provides evidence of Isiac afterlife beliefs outside Apuleius's work. It explicitly says that because the devotee was initiated into the mysteries of the goddess, he did not "walk the dark road of the Acheron" but "ran to the havens of the blessed."[85][Note 2]

Afterlife beliefs in the Isis cult were probably connected with Osiris. The ancient Egyptians believed that Osiris lived on in the Duat after death, thanks in part to Isis's help, and that after their deaths they could be revived like him with the assistance of other deities, including Isis. These beliefs may well have carried over into the Greco-Roman Isis cult.[67][Note 3] The symbolism found in Lucius's first initiation, with its references to death and to the sun in the Egyptian underworld, suggests that it involved Osirian afterlife beliefs, even though Osiris is not mentioned in the description of the rite.[88] As Robert Turcan puts it, when Lucius is revealed to the crowd after his initiation he is "honoured almost like a new Osiris, saved and regenerated through the ineffable powers of Isis. The palms radiating from his head were the signs of the Sun triumphing over death."[89]

Influence on other traditions[editar]

Possible influence on Christianity[editar]

The mysteries of Isis, like those of other gods, continued to be performed into the late fourth century CE. Toward the end of the century, however, Christian emperors increasingly restricted the practice of non-Christian religions, which they condemned as "pagan".[90] Mystery cults thus died out near the start of the fifth century.[91] They existed alongside Christianity for centuries before their extinction, and some elements of their initiations resembled Christian beliefs and practices. As a result, the possibility has often been raised that Christianity was directly influenced by the mystery cults.[92] Evidence about interactions between Christianity and the mystery cults is poor, making the question difficult to resolve.[93]

Most religious traditions in the Greco-Roman world centered on a particular city or ethnic group and did not require personal devotion, only public ritual. In contrast, the cult of Isis, like Christianity and some other mystery cults, was made up of people who joined voluntarily, out of their personal commitment to a deity that many of them regarded as superior to all others.[94] Christianity has its own initiation ritual, baptism, and beginning in the fourth century, Christians began to refer to their sacraments, like baptism, with the word mysterion, the Greek term that was also used for a mystery rite.[95] In this case, the word meant that Christians did not discuss their most important rites with non-Christians who might misunderstand or disrespect them. Their rites thus acquired some of the aura of secrecy that surrounded the mystery cults.[96] Furthermore, if Isiac initiates were thought to benefit in the afterlife from Osiris's death and resurrection, this belief would parallel the Christian belief that the death and resurrection of Jesus make salvation available to those who become Christians.[97]

Even in ancient times these similarities were controversial. Non-Christians in the Roman Empire in the early centuries CE thought Christianity and the mystery cults resembled each other. Reacting to these claims by outsiders, early Christian apologists denied that these cults had influenced their religion.[98] The 17th-century Protestant scholar Isaac Casaubon brought up the question again by accusing the Catholic Church of deriving its sacraments from the rituals of the mystery cults. Charles-François Dupuis, in the late 18th century, went further by claiming that all Christianity originated in the mystery cults. Intensified by religious disputes between Protestants, Catholics, and non-Christians, the controversy has continued to the present day.[99]

Some scholars have specifically compared baptism with the Isiac initiation described by Apuleius. Before the early fourth century CE, baptism was the culmination of a long process, in which the convert to Christianity fasted for the forty days of Lent before being immersed at Easter in a cistern or natural body of water. Like the mysteries of Isis, then, early Christian baptism involved a days-long fast and a washing ritual. Both fasting and washing were common types of ritual purification found in the religions of the Mediterranean, and Christian baptism was specifically derived from the baptism of Jesus and Jewish immersion rituals. Therefore, according to Hugh Bowden, these similarities come from the shared religious background of Christianity and the Isis cult, not from the influence of one tradition upon the other.[95]

Similarly, the sacred meals shared by the initiates of many mystery cults have been compared with the Christian rite of communion.[100] For instance, the classicist R. E. Witt called the banquet that concluded the Isiac initiation "the pagan Eucharist of Isis and Sarapis".[101] However, feasts in which worshippers ate the food that had been sacrificed to a deity were a nearly universal practice in Mediterranean religions and do not prove a direct link between Christianity and the mystery cults. The most distinctive trait of Christian communion—the belief that the god himself was the victim of the sacrifice—was not present in the mystery cults.[100]

Bowden doubts that afterlife beliefs were a very important aspect of mystery cults and therefore thinks their resemblance to Christianity was small.[102] Jaime Alvar, in contrast, argues that the mysteries of Isis, along with those of Mithras and Cybele, did involve beliefs about salvation and the afterlife that resembled those in Christianity. But, he says, they did not become similar by borrowing directly from each other, only by adapting in similar ways to the Greco-Roman religious environment. He says: "Each cult found the materials it required in the common trough of current ideas. Each took what it needed and adapted these elements according to its overall drift and design."[103]

Influence in modern times[editar]

Motifs from Apuleius' description of the Isiac initiation have been repeated and reworked in fiction and in esoteric belief systems in modern times, and they thus form an important part of the Western perception of ancient Egyptian religion.[105] People reusing these motifs often assume that mystery rites were practiced in Egypt long before Hellenistic times.[106]

An influential example is the 1731 novel Sethos by Jean Terrasson. Terrasson claimed he had translated this book from an ancient Greek work of fiction that was based on real events. The book was actually his own invention, inspired by ancient Greek sources that assumed Greek philosophy had derived from Egypt. In the novel, Egypt's priests run an elaborate education system like a European university.[107] To join their ranks, the protagonist, Sethos, undergoes an initiation presided over by Isis, taking place in hidden chambers beneath the Great Pyramid of Giza. Based on Lucius' statement in Metamorphoses that he was "borne through all the elements" during his initiation, Terrasson describes the initiation as an elaborate series of ordeals, each based on one of the classical elements: running over hot metal bars for fire, swimming a canal for water, and swinging through the air over a pit.[108][Note 4]

William Warburton's treatise The Divine Legation of Moses, published from 1738 to 1741, included an analysis of ancient mystery rites that drew upon Sethos for much of its evidence.[110] Assuming that all mystery rites derived from Egypt, Warburton argued that the public face of Egyptian religion was polytheistic, but the Egyptian mysteries were designed to reveal a deeper, monotheistic truth to elite initiates. One of them, Moses, learned this truth during his Egyptian upbringing and developed Judaism to reveal it to the entire Israelite nation.[111]

Freemasons, members of a European fraternal organization that attained its modern form in the early eighteenth century, developed many pseudohistorical origin myths that traced Freemasonry back to ancient times. Egypt was among the civilizations that Masons claimed had influenced their traditions.[112] After Sethos was published, several Masonic lodges developed rites based on those in the novel. Late in the century, Masonic writers, still assuming that Sethos was an ancient story, used the obvious resemblance between their rites and the initiation of Sethos as evidence of Freemasonry's supposedly ancient origin.[113] Many works of fiction from the 1790s to the 1820s reused and modified the signature traits of Terrasson's Egyptian initiation: trials by three or four elements, often taking place under the pyramids. The best-known of these works is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's 1791 opera The Magic Flute, in which the main character, Tamino, undergoes a series of trials overseen by priests who invoke Isis and Osiris.[114]

The Freemason Karl Leonhard Reinhold, in the 1780s, drew upon and modified Warburton's claims in an effort to reconcile Freemasonry's traditional origin story, which traces Freemasonry back to ancient Israel, with its enthusiasm for Egyptian imagery. He claimed that the sentence "I am that I am", spoken by the Jewish God in the Book of Exodus, had a pantheistic meaning. He compared it with an Egyptian inscription on a veiled statue of Isis recorded by the Roman-era authors Plutarch and Proclus, which said "I am all that is, was, and shall be," which led him to believe that Isis was a pantheistic personification of Nature. According to Reinhold, it was this pantheistic belief system that Moses imparted to the Israelites, so that Isis and the Jewish and Christian conception of God shared a common origin.[115]

In contrast, some people in the wake of the dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution used the imagery of a pantheistic Isis to represent their opposition to the clergy and to Christianity in general.[116] For instance, an esoteric fraternal organization in Napoleonic France, the Sophisian Order, regarded Isis as their tutelary deity. To them, she symbolized both modern scientific knowledge—which hoped to uncover Nature's secrets—and the mystical wisdom of the ancient mystery rites. The vague set of esoteric beliefs that surrounded the goddess offered an alternative to traditional Christianity.[117] It was during this anticlerical era that Dupuis claimed that Christianity was a distorted offshoot of ancient mystery cults.[118][119]

Various esoteric organizations that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as the Theosophical Society and the Ancient and Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, repeated the beliefs that had originated with Sethos: that Egyptians underwent initiation within the pyramids and that Greek philosophers were initiates who learned Egypt's secret wisdom.[120] Esoteric writers influenced by Theosophy, such as Reuben Swinburne Clymer in his 1909 book The Mystery of Osiris and Manly Palmer Hall in Freemasonry of the Ancient Egyptians in 1937, also wrote of an age-old Egyptian mystery tradition.[121] An elaborate example of these beliefs is the 1954 book Stolen Legacy by George James, which claims that Greek philosophy was built on knowledge stolen from the Egyptian school of initiates. James imagined this mystery school as a grandiose organization with branches on many continents, so that the purported system of Egyptian mysteries shaped cultures all over the world.[122]

Notes and citations[editar]

- Notes

- ↑ Both Plutarch, in De Iside et Osiride 28, and Tacitus, in Histories 4.83, say that Timotheus, a member of the Eumolpid family that oversaw the Eleusinian Mysteries, helped establish Serapis as a patron god in the court of the Ptolemies. He could have introduced elements of the Eleusinian Mysteries into the worship of Isis at the same time.[18]

- ↑ Details of this inscription are found in Laurent Bricault (2005), Recueil des inscriptions concernant les cultes isiaques 308/1201, and Richard W. V. Catling and Nikoletta Kanavou (2007), "The Gravestone of Meniketes Son of Menestheus: 'IPrusa' 1028 and 1054", in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, volume 163.

- ↑ The gods of some other mystery cults, such as Dionysus and Attis, also died and were seemingly resurrected in myth. Along with Osiris, these gods were once analyzed as members of a category of "dying and rising gods" who had the power to overcome death.[86] Scholars in the early 20th century often assumed that these cults all believed that the initiate would die and be reborn like the god to whom they dedicated themselves. These gods and their myths are now known to be more different from each other than was once thought, and some may not have been resurrected at all.[87]

- ↑ Terrasson did not include a trial by the fourth element, earth, possibly because the initiation's underground setting made it seem superfluous. Authors who imitated Terrasson's description of the Egyptian initiation included a trial by earth as well.[109]

- Citations

- ↑ Brenk, Frederick, "'Great Royal Spouse Who Protects Her Brother Osiris': Isis in the Isaeum at Pompeii", in Casadio y Johnston, 2009, pp. 225–229

- ↑ Burkert, 1987, p. 11

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, pp. 14–18, 23–24

- ↑ Burkert, 1987, p. 2

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, pp. 29–31

- ↑ a b Bremmer, 2014, pp. 5–16

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, pp. 105, 130

- ↑ Casadio, Giovanni, and Johnston, Patricia A., "Introduction", in Casadio y Johnston, 2009, p. 7

- ↑ a b Burkert, 1987, pp. 40–41

- ↑ O'Rourke, Paul F., "Drama", in Redford, 2001, pp. 408–409

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, pp. 110–111

- ↑ a b Burkert, 2004, pp. 87–88, 98

- ↑ Hornung, 2001, p. 1

- ↑ Hornung, 2001, pp. 19–23

- ↑ Tiradritti, 2005, pp. 214–217

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 6, 10

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 58–61, 187–188

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, p. 59

- ↑ Pakkanen, 1996, pp. 80–82

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, pp. 111–114

- ↑ a b c Bremmer, 2014, pp. 113–114

- ↑ Burkert, 1987, p. 41

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, p. 116

- ↑ Griffiths, 1970, pp. 390–391

- ↑ Hornung, 2001, p. 67

- ↑ Venit, Marjorie S. "Referencing Isis in Tombs of Graeco-Roman Egypt: Tradition and Innovation", in Bricault y Versluys, 2010, pp. 90, 119

- ↑ Burkert, 1987, p. 97

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, pp. 71–93

- ↑ a b Bowden, 2010, pp. 166–167

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 336–337

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, p. 114

- ↑ Harrison, 2000, p. 11

- ↑ a b Bowden, 2010, pp. 179–180

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, pp. 3–6

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 342–343

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, p. 133

- ↑ a b c Griffiths, 1975, pp. 95–97

- ↑ Turcan, 1996, p. 119

- ↑ Bøgh, 2015, p. 278

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, pp. 118–119

- ↑ Frankfurter, 1998, pp. 255–256

- ↑ a b c Griffiths, 1975, p. 99

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 181–183

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, pp. 119–120

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, pp. 286–291

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 339–340

- ↑ Translated by J. Arthur Hanson, quoted in Alvar, 2008, p. 123

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 340–341

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, pp. 14, 121–124

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, pp. 299–301

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, p. 124

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, pp. 99–101

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, pp. 103–109, 341–343

- ↑ Burkert, 1987, pp. 69–74

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, pp. 44–46, 213–214

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, pp. 1, 216

- ↑ a b Bremmer, 2014, pp. 123–124

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, pp. 21–22

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, pp. 296–297, 308

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, pp. 303–306

- ↑ a b Bremmer, 2014, p. 122

- ↑ a b Griffiths, 1975, pp. 301–303

- ↑ Pachis, 2012, pp. 88–91

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, p. 283

- ↑ Pachis, 2012, pp. 81–91

- ↑ a b Gasparini, 2011, pp. 706–708

- ↑ a b Brenk, Frederick, "'Great Royal Spouse Who Protects Her Brother Osiris': Isis in the Isaeum at Pompeii", in Casadio y Johnston, 2009, pp. 217–218

- ↑ Harrison, 2000, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, p. 178

- ↑ Bøgh, 2015, pp. 278, 281–282

- ↑ Beard, North y Price, 1998, pp. 307–308

- ↑ Burkert, 1987, pp. 46–50

- ↑ Bøgh, 2015, pp. 264–273

- ↑ Bøgh, 2015, pp. 275, 280–286

- ↑ Burkert, 1987, p. 40

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, pp. 168, 177

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 343–344

- ↑ a b Alvar, 2008, pp. 122–125, 133–134

- ↑ MacMullen, 1981, pp. 53–57

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, p. 133

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, p. 77

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, p. 134

- ↑ MacMullen, 1981, pp. 53, 171

- ↑ Beard, North y Price, 1998, p. 290

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, pp. 121–122

- ↑ Casadio, Giovanni, and Johnston, Patricia A., "Introduction", in Casadio y Johnston, 2009, pp. 11–15

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 33–35

- ↑ Griffiths, 1975, pp. 297–299

- ↑ Turcan, 1996, p. 121

- ↑ Bricault, 2014, pp. 327–329, 356–359

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, pp. 210–211

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, p. 13

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 392–393

- ↑ Beard, North y Price, 1998, pp. 245, 286–287

- ↑ a b Bowden, 2010, pp. 208–210

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, pp. 161–163

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 133–134, 399–401

- ↑ Bremmer, 2014, pp. 156–160

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 386–392

- ↑ a b Alvar, 2008, pp. 228–231, 414–415

- ↑ Witt, 1997, p. 164

- ↑ Bowden, 2010, p. 24

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 419–421

- ↑ Assmann, 1997, p. 134–135

- ↑ Hornung, 2001, pp. 118, 195–196

- ↑ Lefkowitz, 1996, pp. 95–105

- ↑ Lefkowitz, 1996, pp. 111–114

- ↑ Macpherson, 2004, pp. 239–243

- ↑ Spieth, 2007, pp. 51–52

- ↑ Macpherson, 2004, pp. 244–245

- ↑ Assmann, 1997, pp. 96–102

- ↑ Macpherson, 2004, pp. 245–246

- ↑ Lefkowitz, 1996, pp. 116–121

- ↑ Macpherson, 2004, pp. 235–236, 248–251

- ↑ Assmann, 1997, pp. 115–125

- ↑ Spieth, 2007, pp. 91, 109–110

- ↑ Spieth, 2007, pp. 17–19, 139–141

- ↑ Hornung, 2001, pp. 132–133

- ↑ Alvar, 2008, pp. 389–390

- ↑ Hornung, 2001, pp. 112–113, 142–143

- ↑ Macpherson, 2004, p. 251

- ↑ Lefkowitz, 1996, pp. xiii–xv, 134–136

Works cited[editar]

- Alvar, Jaime (2008) [2001]. Romanising Oriental Gods: Myth, Salvation, and Ethics in the Cults of Cybele, Isis, and Mithras. Translated and edited by Richard Gordon. E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13293-1.

- Assmann, Jan (1997). Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-58738-0.

- Beard, Mary; North, John; Price, Simon (1998). Religions of Rome, Volume I: A History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31682-8.

- Bøgh, Birgitte (2015). «Beyond Nock: From Adhesion to Conversion in the Mystery Cults». History of Religions 54 (3). JSTOR 678994.

- Bowden, Hugh (2010). Mystery Cults of the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14638-6.

- Bremmer, Jan N. (2014). Initiation into the Mysteries of the Ancient World. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-029955-7.

- Bricault, Laurent; Versluys, Miguel John, eds. (2010). Isis on the Nile: Egyptian Gods in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt. Proceedings of the IVth International Conference of Isis Studies, Liège, November 27–29, 2008. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18882-2.

- Bricault, Laurent (2014). «Gens isiaca et la identité polythéiste à Rome à la fin du IVe s. apr. J.-C.». En Bricault, Laurent; Versluys, Miguel John, eds. Power, Politics and the Cults of Isis: Proceedings of the Vth International Conference of Isis Studies, Boulogne-sur-Mer, October 13–15, 2011 (en french). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-27718-2.

- Burkert, Walter (1987). Ancient Mystery Cults. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03387-0.

- Burkert, Walter (2004). Babylon, Memphis, Persepolis: Eastern Contexts of Greek Culture. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01489-3.

- Casadio, Giovanni; Johnston, Patricia A., eds. (2009). Mystic Cults in Magna Graecia. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71902-6.

- Frankfurter, David (1998). Religion in Roman Egypt: Assimilation and Resistance. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3847-9.

- Gasparini, Valentino (2011). «Isis and Osiris: Demonology vs. Henotheism?». Numen 58 (5/6). JSTOR 23046225.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn, ed. (1970). Plutarch's De Iside et Osiride. University of Wales Press.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn, ed. (1975). Apuleius, the Isis-book (Metamorphoses, book XI). E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04270-4.

- Harrison, S.J. (2000). «Apuleius, Aelius Aristides and Religious Autobiography». Ancient Narrative 1.

- Hornung, Erik (2001). The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3847-9.

- Lefkowitz, Mary (1996). Not Out of Africa: How Afrocentrism Became an Excuse to Teach Myth as History. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-09838-5.

- MacMullen, Ramsay (1981). Paganism in the Roman Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02984-0.

- Macpherson, Jay (2004). «The Travels of Sethos». Lumen: Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies 23.

- Pachis, Panayotis (2012). «Induction into the Mystery of 'Star Talk': The Case of the Isis-Cult During the Graeco-Roman Age». Pantheon: Journal for the Study of Religions 7 (1).

- Pakkanen, Petra (1996). Interpreting Early Hellenistic Religion: A Study Based on the Mystery Cult of Demeter and the Cult of Isis. Foundation of the Finnish Institute at Athens. ISBN 978-951-95295-4-7.

- Redford, Donald B, ed. (2001). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Spieth, Darius A. (2007). Napoleon's Sorcerers: The Sophisians. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-957-0.

- Tiradritti, Francesco (2005). «The Return of Isis in Egypt: Remarks on some statues of Isis and on the diffusion of her cult in the Greco-Roman World». En Hoffmann, Adolf, ed. Ägyptische Kulte und ihre Heiligtümer im Osten des Römischen Reiches. Internationales Kolloquium 5./6. September 2003 in Bergama (Türkei). Ege Yayınları. ISBN 978-1-55540-549-6.

- Turcan, Robert (1996) [1992]. The Cults of the Roman Empire. Translated by Antonia Nevill. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20046-8.

- Witt, R. E. (1997) [1971]. Isis in the Ancient World. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5642-6.

Further reading[editar]

- Assmann, Jan; Ebeling, Florian, eds. (2011). Ägyptische Mysterien. Reisen in die Unterwelt in Aufklärung und Romantik. Eine kommentierte Anthologie (en german). C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-62122-2.

- Baltrušaitis, Jurgis (1967). La Quête d'Isis: Essai sur la légende d'un mythe (en french). Olivier Perrin.

- Bommas, Martin (2005). Heiligtum und Mysterium. Griechenland und seine ägyptischen Gottheiten (en german). von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-3442-6.

- Bricault, Laurent (2013). Les Cultes Isiaques Dans Le Monde Gréco-romain (en french). Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 978-2-251-33969-6.

- Dunand, Françoise; Philonenko, Marc; Benoit, André; Hatt, Jean-Jacques (1975). Mystères et syncrétismes (en french). Éditions Geuthner.

- Fredouille, Jean-Claude, ed. (1975). Apulei Metamorphoseon, liber XI = Métamorphoses, livre XI (en french). Presses universitaires de France.

- Hanson, J. Arthur, ed. (1996). Metamorphoses (The Golden Ass), Volume II: Books 7–11. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99498-0.

- Keulen, Witse; Egelhaaf-Geiser, Ulrike, eds. (2015). Apuleius Madaurensis Metamorphoses, Book XI: Text, Introduction and Commentary. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-26920-0.

- Kleibl, Kathrin (2009). Iseion: Raumgestaltung und Kultpraxis in den Heiligtümern gräco-ägyptischer Götter im Mittelmeerraum (en german). Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-88462-281-0.

- Merkelbach, Reinhold (2001). Isis regina, Zeus Sarapis: die griechisch-ägyptische Religion nach den Quellen dargestellt (en german). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-598-77427-0.

External links[editar]

- Lucius Apuleius: The Golden Ass, Book XI, translated by A. S. Kline